by Paul Budden

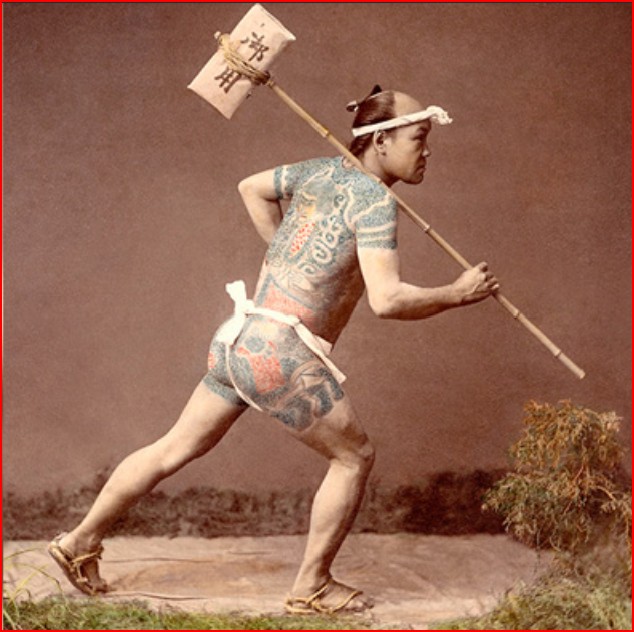

Namba Aruki (or Namba Walking) was the running and walking style famously used by the express runners (Hikyaku 飛脚) during Japan’s Edo Period (1603–1868). These runners formed the lifeline of government communications, tasked with carrying messages swiftly between Edo (modern Tokyo) and the provinces. Typically, they travelled in pairs: one carrying a pole with a package or message box, the other holding a lantern marked “Official Business” (公用). Astonishingly, they could cover the roughly 480 kilometres (300 miles) from Edo to Kyoto in just six to eight days.

Given the immense physical demands of this role, it is only natural that a more efficient style of movement evolved—something less fatiguing and more economical in energy. In the muddy streets of Edo, under the weight of packages, swords, and centuries of tradition, Namba Aruki was born. Silent and precise, it resembled the refined control of the sword arts themselves.

This unique style was not limited to couriers. Namba Aruki proved practical for anyone wearing traditional clothing such as the kimono, where minimising upper body movement prevented the fabric from bunching or wrinkling. It was equally helpful for those walking in traditional footwear like zori and geta, as it reduced splashing mud onto one’s hakama or passersby. For practitioners of the sword arts, Namba Aruki kept the Katana steady, preventing the sword from swinging awkwardly with each step. This made walking with a sheathed blade more comfortable and allowed for faster, more controlled drawing techniques.

In classical Japanese martial arts, particularly within the Koryu, Namba Aruki is more than efficient—it is essential. Although many modern arts have moved away from it, disciplines such as kendo and aikido can still benefit from its principles. In systems like the Itto-ryu Mizoguchi-ha, Namba Aruki plays a fundamental role in Kata execution and footwork. Proper use of the style aligns with the body’s natural biomechanics, enhancing balance, stamina, and efficiency. It reduces wasted motion, keeps posture stable, coordinates power between the limbs and hips, and allows movement to remain smooth and controlled without unnecessary strain.

Why, then, did Namba Aruki disappear? Several theories exist. One significant factor was the influence of Western military instruction. With the introduction of conscription during the Meiji era, soldiers were trained to march in the Western style, moving opposite arms and legs in rhythm. Over time, this became the normalised gait in Japanese society. As Japan modernised, clothing, footwear, and posture shifted as well. The banning of swords, along with the decline in daily use of kimono and geta, made the Namba style less practical. Without the functional demands that once shaped it—such as long-distance courier work, sword-bearing, or muddy streets—Namba Aruki naturally fell out of everyday use.

Some researchers believe that Namba Aruki was always somewhat exclusive, practised mainly by express runners, samurai, or the upper classes who received formal training. Others argue that it was once more widespread. Given the limited historical documentation, the truth may lie somewhere between. What is clear, however, is that Namba Aruki was a learned technique rather than a naturally occurring walking style.

Reviving Namba Aruki today offers more than just insight into efficient walking or martial training. It provides a glimpse into the refined, intentional movement that characterised life in the Edo period. For martial artists, historians, or enthusiasts of traditional Japanese culture, exploring this style is a way of stepping back into a piece of embodied wisdom that time has nearly forgotten.

From The Secret Sword – A Study of Itto-ryu Mizoguchi-ha ‘Chapter One’

You can find more information from William Reed on Namba Walking at the BudoJapan.com website:

William Reed’s Samurai Walk & Nanba Self-Protection

Copyright © 2025 Paul Budden